- Home

- Aida Kouyoumjian

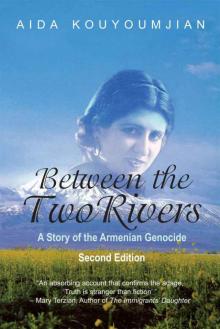

Between the Two Rivers: A Story of the Armenian Genocide Page 3

Between the Two Rivers: A Story of the Armenian Genocide Read online

Page 3

What a day! Adrine promised to give her food tomorrow. Her sores pained her less after soaking in the river. The foliage quieted her grumbling stomach.

She wanted to stay in the grave and guard her cache forever.

What if Romella, as promised, came back to fetch her, but found no trace of her in the khan?

2—The Last Link

The old, empty gravesite became Mannig’s life-saving treasure.

It was dependable. Unlike Adrine’s promise for a chunk of bread, often unrealized, her grave always guaranteed greens to pacify her hunger. Romella’s promise of a home, on the other hand, remained empty, since she failed to return to the khan after having secured employment for herself.

Mannig knew the grave would never abandon her. On days when she failed to find something to eat, the greens in the pit of the grave guaranteed a lessening of her hunger. Often, when she needed solace from the filth of the khan, jammed with starving orphans, the grave offered a hideaway and fresh air. She guarded her find, never to disclose its location to anyone.

At night, she joined the other orphans in the dilapidated khan. Huddled under her frayed quilt, she dreamed about luxury in her grave. In the mornings, she rose before anyone else. Her emaciated, blanched cheeks accentuated her almond-shaped, large brown eyes below elongated eyebrows. As usual, her bristly lashes were stuck shut by mucous, filth and debris. She scraped off the hardened scum, just enough to separate her eyelids. As soon as she could see, she dashed out to scavenge, long before the other children of the khan awoke.

One day, after foraging the alleys, she was driven by the dry, cold wind to return to the khan for shelter. The dying sun of dusk cast an elongated shadow ahead of her. She noticed a figure leaning against the mud brick wall of the khan. Her silhouette resembled Romella’s, except for the stance. This person reminded her of Romella’s warning: “Quiet hands make a restful heart, but a restless heart makes busy hands.” The figure stood useless as a broken spindle. Head downcast, she leaned one foot on the wall and rested blistered hands across her folded arms. Her olive complexion looked pasty and tired. Her demeanor whispered the pain of one who bore sad news. Unlike the youthful woman in her early twenties that she was, she slumped low with the burdens of the aged.

Nevertheless, it was Romella.

Mannig wanted to dash toward her, to be hugged and loved again by the caressing hands of the one who had become her substitute mother. Yes, she had adored Miss Romella since her kindergarten days in Adapazar, and she knew that without Romella’s guidance in the desert, surviving the death march would have been impossible. Mannig craved the motherly love she found only in Romella. Solitude depleted hope. Staying alive wore her down. Surviving in Mosul by her own wits exhausted her.

Seeing Romella after an absence of several months froze Mannig’s legs. Something held the girl back from covering her with kisses. Delaying the dissappointed words on Romella’s lips sustained her dream of a new life, of being a family in a home and gorging on food without ever stopping.

Romella raised her head and adjusted her scarf. The veins in her eyes accentuated her glazed look. Upon seeing Mannig, she straightened her posture.

Eyes cast down, Mannig shuffled her feet. As each step shortened the distance between them, the pounding of her heart increased. Internal lightning in her head threatened to ignite a thunderstorm within. She dreaded an end to her hopes.

“Cherie! Cherie!” Romella said, with outstretched arms—an endearing gesture Mannig adored, because it reminded her of her mama.

Mannig lurched into Romella’s arms—relished the sturdy grip on her shoulders. She’s like Mama.

“You know what I am going to tell you,” she whispered, brushing a kiss on Mannig’s forehead. “I thank Jesus for blessing you with such intuition. When I promised your dying mother to take care of you, I failed to foresee how the promise itself became the force behind my own endurance. If you died, God forbid, I would, too. Believe me. I never doubted that you fueled the energy in my life. You still do. My promise to your mother kept me alive, and your presence inspired me to overcome hardships, and … ”

Mannig knew bad news lay ahead. People refrained from talking these days. Talking required energy, and hungry people kept silent unless calamity loomed. She concentrated on the pleasantries. When she needed solace, remembering nice comments consoled her soul. Hear Romella’s words … remember them. In the midst of loneliness, such words become the friends of a lost heart.

Romella listed Mannig’s endearing characteristics and delayed revealing the bad news. Praises coming from her kindergarten teacher delighted her. She resolved to store them in her heart. She cherished the moment.

“And you are jarbeeg,” Romella continued, meaning that she was street smart. “Look at you. How you have grown! I admire your perseverance. You haven’t perished like the others because you didn’t give up. You are different. You’re smart enough to care for yourself. I am sure it will be you, not me, who finds a home for you.” Energy flowed in her voice, but there was no luster in her eyes. “I am lucky. I happen to fill the needs of the family I serve.” She cuddled Mannig’s head against her chest and brushed her hair with her fingers.

Mannig’s body tingled. The caressing fingers on her scalp recalled Mama’s style. She separated a stringy strand of chestnut hair to the right and another strand to the left. Mannig savored the blissful feeling, especially when Romella traced her widow’s peak. Sweetness oozed in her words. “You will become a very pretty maiden one day. And you will be luckier than me, cherie.”

“Luckier?”

“Help for the orphans is coming,” Romella said, wrapping her floral robe around her hips. She then sat on her heels by the entrance of the khan. “I have heard that important Armenians from Baghdad and Basra are coming to save the children.” She tugged at Mannig’s burlap dress and prompted her to sit by her. “They’re coming to Mosul to collect the orphans. They will surely find you, house and feed you.”

“They will really give me food?” Mannig exclaimed in disbelief.

“I am sure!”

“When, when, when?”

“I don’t know when. But, they’re coming, I’m sure.”

Romella’s ensuing silence, albeit momentary, allowed Mannig to savor the thought of her stomach stuffed with food.

“In the meantime,” Romella continued, “maybe an Arab family will make use of you. Perhaps you can do something for them. Yes, you must find a family and get out of this khan.”

“I want to be with you. Won’t you take me into your home?” Mannig mumbled, expecting to be refused.

Romella leaned forward and whispered. “The khatoon of my family is very strict. If things are not done her way, she lashes the servants and then wails sky-high for the whole neighborhood to hear how things aren’t done right by her maids. I, myself, cannot seem to do much to her liking.” She rolled up her sleeve, exposing a long scar, with the scab still hanging from some parts.

Mannig glared.

“Find an Arab family,” Romella insisted, rolling down her sleeve. “Be sure that it’s an Arab family. Don’t be tutoum kulukh, a pumpkin head like me … by getting into a Kurdish or Turkomen family. Those ethnic enclaves dislike Armenians—they remind me of the Turks sometimes.”

No need to explain. The word Turks aroused dread in Mannig’s heart. Still enslaved by the memory of the horrific treatment at the gendarmes’ hands, she failed to erase images of her massacred family. “This is for you,” Romella said and removed the brown sweater from her shoulders.

Tongue-tied, Mannig let Romella drape it around her neck. The warmth was instantaneous, the pleasure only over-shadowed by Romella’s compliments. Assuming a self-proclaimed grandeur, Mannig raised her head and stood erect; she visualized herself as a powerful person, capable of conquering any calamity.

“Next time I may bring a woolen coat,” Romella continued. “I heard that Barone Mardiros, one of those philanthropists from Baghdad, is collecting warm

clothing for the....”

Mannig’s thoughts hovered over her newly acquired garment. Her flesh and bones relaxed in contentment. She owned a much-needed shield from chills to forage Mosul alleys with confidence. The future Romella described—of a generous man from an unfamiliar-sounding city—was too far from Mannig’s reality. She only cared about the present.

“I also brought some bread,” Romella said, rising and pulling Mannig up with her. She retrieved a round loaf from the folds of her robe, broke it in half and exposed slivers of dates in its center. “The bread I bring for you next time will contain meat and onions kneaded into it. Definitely. By then, of course, you may be fostered by the philanthropists of the Middle East Relief group. So you won’t need anything.”

Surprise exceeded Mannig’s vocabulary, also her reaction to the bread. She grabbed it and ferociously bit into it. With her mouth full and crumbs sticking onto her lips, she sputtered out. “Will you come here again?”

“It will be difficult to sneak out soon. But I will, sometime. I miss you too much.”

Mannig wanted to say, I miss you too, but another morsel of bread took precedence in her thoughts. She devoured the bites so fast her palate scarcely discerned the sweetness of the dates, yet she felt crumbling grains of the crust on her lips. Carefully, her fingertip brushed each grain into her mouth. Then she licked her upper and lower lips clean. Not a single speck must be wasted.

“I must go now,” Romella said and approached Mannig with open arms.

Her mouth still full, Mannig remained speechless. She let Romella embrace her goodbye. She could not bear another separation. Repeat abandonment should have overwhelmed her, but the food in her stomach calmed her anxiety.

Romella had not forgotten her, after all. She still cared for her, just as she had done in the scorching desert when everything under the sun melted—everything except the memory of massacred families. For two years, through horror and despair, her kindergarten teacher from Adapazar and she had become partners in pain and misery. Now, in famine-stricken Mosul, they were becoming counterparts in self-reliance.

With half a loaf in her stomach, the other tucked inside the sweater, how tutoum kulukh of her to think she was abandoned! Romella had promised to return, and had. A teacher’s word should never be doubted! She must remember everything Romella said, especially today, to secure an Arab family for herself until the important people came from Baghdad, loaded with clothes and food for the orphans. Romella named a Barone so-and-so. What was he called? His name floated by while Mannig was concentrating on the food in her mouth—the only thing that mattered to her. She pinched herself. Next time I will focus on the conversation and what’s in my mouth.

Romella called her jarbeeg. She must live up to her reputation—become street smart. Tomorrow.

3—Barone Mardiros

Close to midnight, weary Mardiros arrived at Sebouh Papazian’s house in Mosul.

The train ride from Baghdad exhausted him. The stop-and-go at each tiny village to disembark and board new passengers tried his patience. The slow train to Mosul frustrated him. I want to be useful. The 300-mile trip stole much precious time from accomplishing his mission. At thirty, he faced new challenges in pursuit of his passion to help the orphans of the desert, an undertaking paradoxical to any of his earlier exploits.

What a change from his previous life!

The youngest son of a wealthy family in Baghdad, Mardiros Kouyoumdjian enjoyed a life of affluence. He had returned from Robert’s College in Constantinople in 1912, an engineer at twenty-two, and divided his time between social revelries and society gatherings. He knew he was handsome and the most eligible bachelor in Baghdad. Poised and refined, he flattered the beautiful and rich and flirted with the respectable young ladies of the upper class. He chuckled to himself, often infuriating his mother, as well as his sisters-in-law, whose diligence in matchmaking he unabashedly snubbed.

When the Big War broke out in 1914, the Kouyoumdjians became restless. In spite of the 2,000-kilometer distance from Constantinople—the seat of the Ottoman rulers—they foresaw imminent disaster. After all, the education of the five brothers in France or England and business enterprises with Allied nations now against the Ottomans and Germany raised their suspicions. They suffered perpetual sleepless nights.

No Kouyoumdjian foresaw the coming deportation of the Armenian communities from Asia Minor, least of all from Kayseri and Talas, the base of their ancestry. When word reached them that one of Mardiros’ sisters and her family had been deported and then massacred along with all the Armenians in Diar Bekir, rage engulfed Mardiros, contradicting his family’s resolve to face fate passively. Realizing the futility of taking his revolver and shooting Ottoman authorities in Baghdad, he devised a secret scheme.

One day in 1916, two years into The Big War, he barged into the Ottoman Millet headquarters in Baghdad.

“I know seven languages, Your Most Esteemed Honor,” Mardiros explained to the Sultan-appointed governor. “I can hear things and relate them to you.” Switching from Turkish to Arabic, he added, “Your Honor, we all want to know what the Arabs are saying about the British and the deals they are cutting with the French. With my Arabic, I can be your spy in the Diyalah region.”

The Governor allowed Mardiros to describe the plan. He assumed allegiance because Mardiros’ father, His Excellency Hagop Kouyoumdjian, had been commended and honored with the title of Pasha by the Sultan for his philanthropic deeds and loyalty to the Ottomans.

“Of course, Effendi, you know the British are in control of Palestinian lands,” Mardiros said—an optimistic rumor articulated by his family in their own parlor. “The Englaizees, the Fransawees and the locals may be cutting a deal in the territories just west of us—only a few kilometers from your seat, Your Honor.”

Encouraged by the governor’s attentiveness to facts he probably already knew, Mardiros continued. “Delegate me, Your Honor, as your representative in the western provinces. I grew up in Felloujah, played with the children of the Arabs surrounding our Qasr and farmlands. I can easily mingle with the Bedouin west of the Euphrates. I have good friends in the desert. Let me be your eyes and ears in the field.”

The governor agreed to a trial period.

Mardiros plunged into his charade.

He replaced his European clothing with a brown-and-white striped dizhdasheh gown and belted his waist with a turquoise-adorned shield for his dagger. He placed a Bedou aggaal and kaffieh on his head and rode his horse to Felloujah, a Kouyoumdjian stronghold along the Euphrates River. From there, he relayed messages to the Governor in Baghdad telling what he heard from the mouths of his own farmhands. He censored the derogatory utterances and included only the mildest grumblings reflecting the Arabs’ dislike of the Ottoman rule over their lands. He didn’t want to appear biased in his reporting. Mardiros knew how to appease the authorities.

He rode his horse to Rumadi and Rutba, two Ottoman outposts, at the edge of the vast desert, ninety kilometers northwest of Baghdad. To further establish his credibility, he telegraphed to the Governor every detail he learned from the local Arabs—nothing more, nothing less.

Soon he gained the Governor’s full confidence and, upon his return to Baghdad, the Governor dispatched Mardiros to Basra, 600 kilometers south.

“Your job in Basra is to infiltrate the insurgents,” the Governor commanded him. “There’s a rumor they are cooperating with the British at the Persian Gulf. We think they will invade our territories from the south.”

“I will pretend to be an insurgent myself,” Mardiros said (controlling a sneer: in fact, he already was one).

Six months into his assignment, Mardiros began sending erroneous messages to the Governor. He distorted many facts to make them appear politically compatible. He intended to manipulate the Ottoman troop distributions and prevent forces from amassing in the South.

“It is only a rumor,” he telegraphed from Basra, emphasizing the word, rumor. “The British, together with Indi

an forces, are gathering by ship in Basra …

“We are in control—STOP

“No need to keep one eye open—STOP”

Another message read:

“The Arabs in Basra don’t want Englaizees on shore—STOP

“The locals will fight if necessary—STOP

“Everyone is geared to crush the enemy—STOP”

The next telegram included more details:

“Some insurgency exists—STOP

“Their number is vastly exaggerated—STOP

“This front remains solidly ours—STOP

“There is no need to worry about Basra, at all,” Mardiros repeated. He added a postscript: “I am off to Najaf—STOP

“More insurgents among the Shiites there—STOP”

He rode his horse northwest from Basra, along the Euphrates River, with his entourage of Ottoman escorts. While mingling amicably with the Arabs near Hillah, in the Babylonian region, he recognized his oldest brother, Karnig, also dressed in the tawny Arab garb, cooperating with local insurgents.

After a brief encounter with a British Officer, clothed in the Arab headgear of the aqaal and kaffieh and known by the Bedouin as Lawrence, the brothers agreed to cooperate in their efforts to deceive the Ottomans full speed ahead.

A Turkish officer in their entourage suspected treason and accused the brothers of being double agents. He spared them instant death in deference to their father’s title of Pasha and imprisoned them in an Ottoman garrison between Hillah and Babylon.

Between the Two Rivers: A Story of the Armenian Genocide

Between the Two Rivers: A Story of the Armenian Genocide