- Home

- Aida Kouyoumjian

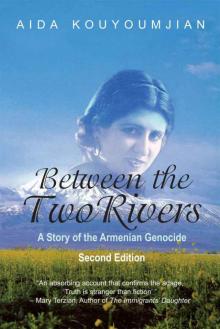

Between the Two Rivers: A Story of the Armenian Genocide

Between the Two Rivers: A Story of the Armenian Genocide Read online

Praise for Between the Two Rivers

“Aida Kouyoumjian’s rich memories of her mother will be a source of great fascination to anyone interested in the Armenian Genocide.”

—Dawn MacKeen, Award-Winning Freelance Journalist

“The book reads like a chapter from One Thousand and One nights. An absorbing account that confirms the adage, ‘Truth is stranger than fiction’ … The author’s visual descriptions touch the senses.”

—Mary Terzian, Author of The Immigrants’ Daughter

“Mannig’s spirit, resourcefulness and courage captivate the reader.”

—Genie Dickerson, Journalist, Washington, D.C.

“I am impressed with how you have woven personal history with solid research. BRAVO!”

—Helene Moussa, Retired scholar of Coptic art/Author of Legacy to Modern Egyptian Art, Toronto, Canada

“I cannot put it away. I knew the story would be incredible. But that is just part of it. The book is also masterfully written, in a very direct and honest manner. It is both touching and thought provoking at the same time. The characters are so alive they seem to have become part of my life. The book is clearly a winner.”

—Artak Kalantarian, son of celebrated Armenian author Artashes Kalantarian and Manager, Seattle Armenians Yahoo Group

“Aida Kouyoumjian moved to America in 1952. The fact that this novel is written in English is a testament to her intellect and very vibrant voice. The book depicts Arabic and Armenian traits and it weaves a carpet for me to get a glimpse of what life was like back then ... Growing up in the ’50s, I remember my parents telling me to finish the food on my plate with “Remember the starving Armenians.’ ”

— Deborah Cooke, Retired editor/published writer travel

“My mind staggers at the disruption of simple human life by the whims and obsessions of others. This is a great book for you to revisit how you see other human beings on the verge of violent and disruptive behavior by those who do not have the right to do so. I just love your book ... It is a labor of love but worth every ounce of your heart and mind you poured into it. You are very gifted as a storyteller.”

—Dr. William Rice, Professor of economics at California State University at Fresno.

“Thank you so much for sharing your mother’s story with the world. You are a wonderful writer. I feel richer knowing you and your family’s story.”

—Vicki Heck, Librarian, Mercer Island Library, Washington

Between the

Two Rivers

A Story of the Armenian Genocide

Second Edition

Aida Kouyoumjian

Published by Coffeetown Press

PO Box 70515

Seattle, WA 98127

For more information go to: www.coffeetownpress.com

www.armenianstory.coffeetownpress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover design by Sabrina Sun

Between the Two Rivers: A Story of the Armenian Genocide

Second Edition

Copyright © 2011 by Aida Kouyoumjian

ISBN: 978-1-60381-111-8 (Trade Paper)

ISBN: 978-1-60381-112-5 (eBook)

Produced in the United States of America

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe my love and dedication for Between the Two Rivers to my mother, Mannig Dobajian Kouyoumdjian. She instilled in me the value of memory—not as a human quality but a privileged responsibility to share. I heard her survival stories in the form of lullabies in Felloujah, Abu-Ghraib, Hillah, Mosul and Baghdad—the locales where my father, Mardiros Kouyoumdjian, was assigned to build a dam or engineer the canal-networks for the Irrigation Department of the Iraqi Government. Her melancholic chants ingrained in me how painful it is to lose one’s family. Her survival stories taught me not to give up—Mannig, living, and I, telling her story in English. When asked, “How long did it take you to publish her memoirs?”

“A lifetime.”

After Mannig immigrated to the United States, she and I spent many hours over a cup of Seattle’s delicious coffee talking about her life. We repeated similar scenarios whenever my sister, Maro Kouyoumjian Rogers of South Carolina, visited us. Eventually, my mom handwrote several stories of her memoirs and, just before her death, in 1985, she recorded a short tape.

You will notice I spelled my father’s surname with the letter ‘d.’ Our family name in Iraq remains under the influence of French spelling, requiring a ‘d’ for its accurate pronunciation. On my arrival in America, I wanted to shorten our long and difficult-to-pronounce name. I dropped the letter 'd.’ My mother and my sister followed my example, but my father, who passed on in Baghdad before he could emigrate from Iraq, retained the traditional spelling—as have most members of our kinfolk in the Diaspora.

Personally knowing the principal individuals of Between the Two Rivers has been my fortune—their names are factual, such as my morkor, Adrine, deidie Sebouh Papazian, and diggin Perouz. The Kouyoumdjians of Felloujah and Baghdad are also identified by their own names. The remaining characters are real, but their names are fictitious. Any resemblance is purely coincidental. My mother spoke of Dikran, Romella, and the sisters from Van, but their true names had faded from her memory.

Thanks to Zola Ross, the founder of the Pacific Northwest Writers Association, for encouraging me to write Mannig’s story and later urged me to enter their annual contest. An award in the non-fiction category inspired me to write of the Armenian Genocide, an issue emotive to living Armenians. Every April 24th, the Republic of Armenia and communities throughout the world commemorate the memory of 1.5–2 millions who were annihilated during World War I. We mourn our loved ones who perished and rejoice with the descendants of survivors whose agonizing stories elucidate and expand our historical knowledge—a continuous renewal of our Armenianness.

My gratitude goes to three award-winners in my critiquing group for their editorial expertise who tracked the progress of my mother’s story to its completion. Joyce Lindsey O’Keefe, Genie Dickerson and Mary Kay Windham graciously guided the flow of the progress of Between the Two Rivers.

Thanks to Jim Farrell for connecting me with Coffeetown Press, and to Michael Lettini, my neighbor, for his assistance with computer glitches.

I value the tacit support of my sons, Armen, Brian, Roger and their families who never prodded me for a publishing date.

My utmost thankfulness goes to our Lord for protecting my mother from the ‘claws of the Ottoman gendarmes’ and for all His goodness toward my family.

September 16, 1916—

To the Government of Aleppo:

It was at first communicated to you that the government, by order of the Jemiet, had decided to destroy completely all the Armenians living in Turkey. . . . An end must be put to their existence, however criminal the measures taken may be, and no regard must be paid to either age or sex nor to conscientious scruples.

—TALAAT PASHA, Minister of the Interior

August 22, 1939—I have given orders to my Death Units to exterminate without mercy or pity men, women, and children belonging to the Polish-speaking race. It is only in this manner that we can acquire the vital territory which we need. After all, who remembers today the extermination of the Armenians?

—ADOLF HITLER

Table of Contents

1—Luxury in the Grave

2—The Last Link

3—Barone Mardiros

4—Jarbeeg

5—Funeral Feasts

6—‘Small Wit, Active Feet’

7—Under Her Wings

8—Beyond Staying Alive

9—It Shall Be April 1, 1906

10—The Telegram

11—Dunk the Chunk and Sip the Soup

12—Do This … Do That

13—Weeping Meeting

14—A Sister among the Arabs

15—Things that Matter

16—Ousted for Sex

17—Another Language

18—A Night at the Church

19—Down the Tigris

20—The Kalak

21—White City

22—Tête-à-Tête

23—Father of the Orphans

24—Not All Good Deeds Meet All Needs

25—Childlike

26—The Ladder of Joy

27—Happiness is …

28—Where is America?

29—To Basra

30—Modern Man

31—New Place, New Awareness

32—The Foxtrot

33—Surprise, Surprise, and Surprise

34—To Jerusalem

35—January 22, 1922

EPILOGUE

GLOSSARY OF FOREIGN WORDS

Historical Highlights of Armenia

WHAT MAKES AN ARMENIAN?

REFERENCES

1—Luxury in the Grave

Mannig breathed freely. Ah, but staying alive—a different story.

Her fear of whips vanished with the disappearance of the gendarmes—this, after they drove her family from their beautiful home in Adapazar, near Constantinople. Three years later, they abandoned the deportees in the middle of the Mesopotamian Desert and disappeared like a mirage.

Mannig wallowed in freedom now. At the age of ten—more likely younger—she depended on her own wits to fend for herself. She had no skills for survival, but eventually emerged profoundly mature by blocking out horrific memories. She managed to remember only a kaleidoscopic Adapazar from her early childhood—twirling in her yellow dress, air swirling between her legs, melodies on Mama’s violin, warmth from the charcoal brazier. I’m alive! My happy days will survive. Like the flickering rays of the hurricane lamp in their parlor, bits and pieces of her family’s devotion helped her survive her grief. Ignoring pain was her way to resist the suffering brought by the annihilation of her loved ones. I must not forget. Who cared if her toe hurt? Foraging for edibles in this famine-stricken city of Mosul absorbed her waking hours.

A chilly November in 1918 summoned a cruel winter in the largest city along the northern shores of the Tigris River. The winds blew in from the rugged Taurus Mountains and swept across the metropolis before cooling the Mesopotamian Desert.

Mannig squinted into a gust of cold wind and shivered. She folded her bare arms and looked at the midday sun. It peeked above the high roofs of the deep alley. Unlike the blistering sun of the desert, this sun barely emitted warmth. Even their sun is weak. She slid her hands inside the wide armholes; the tawny burlap sack dangled down her bony shoulders.

Ahkh! She yelped at her chilled hands, as her fingertips crawled up and around her hunger-distended belly. Why is my empty stomach so large? In Adapazar, her family had laughed when she sucked in her belly to touch her back—even after stuffing herself with mante, Mama’s specialty of pastry squares stuffed with ground spicy lamb. Her tummy had been flat when she lived with the Bedouin, too. They had sheltered her in their tent for several months after they rescued her from the scorching sun. She had gobbled Arabic bread stuffed with zesty onions and never hungered, but her stomach had been flat then. Now, she hardly found anything to send down to her stomach, yet when she wanted to see her toes, a protruding belly hindered the view.

Mannig’s stomach growled—a cue to look for food morsels.

A wad of cloth in a pile of rubbish steered her to forage down the alley. A hop across the open sewer-ditch, and she pulled on the rag. Could it be a coat?

Before salvaging it, she scanned her surroundings for other scavengers preparing to pounce on her. None emerged. Bent in half, she freed a piece of cord from the trash and mud. Disgusted at such a useless find, she almost discarded it, and then she changed her mind—a find is a find, in spite of its stink. She belted the rotten sack and covered her body with it. Ahkh! She shuddered. The rotten coarse fibers of the garment scratched against her bare skin; it needled the sores on her chest and back. She pressed her exposed arms close to her ribs and snuggled her hands in her armpits, a stance she often adopted to prevent her budding breasts from peeking from the ragged armholes.

Mannig sauntered into an unfamiliar alley. Chatter, clatter, and smells enticed her deeper into it. A whiff of yeast wafted from the billowing smoke of a chimney. Like the Adapazar bakery? She dashed to the adobe walls and peered through a window-like hole. “Khattir Allah, Joo’aaneh,” she sniffed and cried. “For God’s sake. I’m hungry.”

“Imshee!” the woman shooed Mannig away. “Scat! We’re all hungry. All of Mosul is starving; millions of us are always hungry.”

I don’t want bread for all of them; I only want a bite for me.

Not far ahead, a prominent minaret pierced the chilly blue sky, and the mu’adthin’s melancholic chant reminded the Muslims of their vows. In Adapazar, the opening scores of Allah-oo-Akbar had aroused Mannig to sing along the prayer of God is great—if not loudly, at least humming along with the clergy’s trills and tremolos. She relished the carefree image of her life four years before.

Adapazar belonged to the past.

In Mosul, hunger squashed other sensations.

Across from the bakery, Mannig lingered over the aroma of the seething sesame oil gusting from fritters over an open fire. Her nostrils flared. She smiled at the Kurdish woman poking the embers.

“Khattir Allah, Joo’aaneh,” she cried, eying the woman.

“Imshee!” the woman shooed Mannig off with her arm and crouched closer to her pan. She readjusted her ocher-checkered scarf around her head. “If I give you food today, my own children will waste away tomorrow.”

Mannig knew the futility of competing with children who had a mother.

She swerved around just when a jeering “Get out of my way!” shout startled her. She barely dodged a ragged fellow tugging at his donkey. She gazed at the animal. Its back curved low under the weighty water sloshing in goat-skin sacks; the protruding ribs framed its back like the mangy dogs scavenging nearby.

She caught her breath. Kheghj esh. Poor donkey! It must be as starved as she.

Her heart thumped in rhythm to the pounding of two coppersmiths. They hammered pretty, shiny bowls a few strikes and then rested to chat with each other.

“We work, and we work,” complained the younger one. “But we haven’t sold anything since the Ottomans retreated from Mosul.”

“Conditions will change as soon as the Englaizees arrive,” the sage said. “They will promote commerce here, just as they are doing in Basra. Hear my words, young man. They are headed this way even as we speak.”

“I wish they would hurry. I want them to drive away the Kurds … and … keep the Turkomen within their separate enclaves.” The youth waved his hammer in the air and struck his bowl. “We want Mosul for us, the Arabs. Those ethnic tribes are stealing our businesses, and soon they will wed our women. I hope the Englaizees will remember that we, the Arabs, helped them in the Big War. Without us, they wouldn’t have crushed the hated Ottomans. When will the English come? ”

No food handout here, Mannig told herself. She ambled by while glancing at their brown striped robes, reminiscent of the Bedouin garments.

“They will come soon,” the sage said, lifting his hammer.

“Sure they will—after we’ve starved and gone,” the youth said just when Mannig caught his glance. “She’s starving too,” he pointed the hammer at her. “But I bet she won’t for long. She’s pretty.”

No one had called her prett

y in four years. It made her feel nice inside. She flashed a smile, but she stopped short when he shifted his stance and grabbed his crotch. He fondled himself while he ogled her.

Nudged by instinct to shield herself, Mannig tucked her elbows in to hide any bare flesh sneaking through the large armholes of her burlap dress. Spurred by survival energy, she dashed round the bend, out of the bazaar, and into a new alley.

No starvelings here? What luck. Scrawny arms dangling from her shoulders like dried cloth, and skeletal legs like useless sticks, she darted from stone to rubbish. Ahkh. Hop, hop: she jumped to alleviate the sharp sting in her infected toe. Zakhnaboot. She stubbed her wound again. It’s never going to heal! To check the damage, she stuck her foot out beyond her malnutrition-distended belly. The toe bled; the gash ached anew. Shoes! I must find shoes … one shoe? But first, I need food, then a coat … and then shoes.

She explored alleys farther beyond the khan, the abandoned inn for caravans that she called home. She needed something to eat before spending the night with the horde of Armenian orphans, all of whom were just like her—scrawny, pathetic, and alone.

In spite of Mannig’s petite stature, she dreamed big. Searching for edibles occupied all her waking breaths, but her heart’s desire nudged for things beyond. She wanted to read and write, like her older sister, Adrine. She fantasized about becoming a teacher, like Miss Romella, her kindergarten tutor in Adapazar.

Between the Two Rivers: A Story of the Armenian Genocide

Between the Two Rivers: A Story of the Armenian Genocide